Introduction

In their essay, “Biblical Images of God as Mother and Spiritual Formation,” Ronald Pierce and Erin Heim seek to “explore and contemplate God’s self-revelation through Scripture’s metaphors of motherhood as they relate to our personal spiritual formation, that is, asking how these metaphors inform, form, and shape our identity as God’s people” (372). The authors hope that Christians, after reading the essay, will “understand better and experience more fully the person [sic] and work of the triune God, Father, Son, and Spirit, who is also portrayed in terms of motherhood” (373). After summarizing the chapter, I will critique the essay for its inadequate and imprecise account of theological language. It will be shown that the chapter does not, in fact, help readers “understand better and experience more fully” the triune God. Rather, the profound lack of theological precision in matters of great weight and consequence leads to a collapsing of important distinctions and thus diminishes understanding rather than deepening it.

Summary

Pierce and Heim begin by sharing their personal experiences with their respective mothers and how such experiences have profoundly influenced their own paths of discipleship. This is followed by a brief but important discussion of “The Triune God and Gender.” Joining the chorus of all orthodox voices throughout church history, Pierce and Heim remind readers that “God is spirit” and, as such, is neither male nor female in terms of having a sexed body. Furthermore, the authors make clear that they will not be advocating for replacing the designation “God the Father” with “God the Parent” or “God the Mother” (374). Alongside the masculine metaphors for God in Scripture, they wish to highlight the feminine imagery, especially that of motherhood. They explain, “Motherhood language predicated of Yahweh in the Hebrew Scriptures is true of the whole Trinity, revealing something just as true about God’s essential nature as masculine metaphors” (375). For Pierce and Heim both the name “Father” and the images of motherhood are metaphorical when spoken of God. It follows, therefore, that God may be referred to as “Mother” in addition to the more common designation of “Father.” They cite Julian of Norwich favorably in this regard: “God is our mother as truly as he is our Father” (375).[1]

The next section of the essay discusses “Metaphor in Scripture and Theology.” The authors’ understanding of the use of metaphorical language in Scripture is of great theological consequence. Pierce and Heim assert, “The majority of the language used of God in Scripture is metaphorical” (376), an assertion that places the biblical naming of God as Father on the same conceptual plane as the metaphors of motherhood spoken of God’s acts in Scripture. Thus, the authors’ stated wish for readers to “inhabit Scripture’s metaphors of God as mother” (377) represents a kind of balance to the supposed tendency to inhabit only the masculine language used for God.

The bulk of the chapter is devoted to exegetical analysis of the motherly metaphors for God used in Scripture. Attempting to follow an explicitly Trinitarian structure, Pierce and Heim first consider “Yahweh, the covenant God of Israel” (379–83), Jesus the Messiah second (383–87), and the Holy Spirit third (387–90).[2] Sustained attention is given to prophetic texts in which Yahweh carries Israel in the womb (Isa 46:3), experiences birth pangs for Israel (Isa 13:6–9), nurtures Israel like a nursing mother (Isa 49:14-15), and cares for Israel like a mother cares for her weaned child (Hos 11:4, 8). Pierce and Heim seek to demonstrate that motherly metaphors communicate profound truths about the love and fierceness of God in his covenantal devotion to his people. Furthermore, the text about Jesus longing for the people of Jerusalem like a hen desires to gather her chicks (Mt 23:37) is considered against a multi-faceted Old Testament background to demonstrate that the use of distinctly feminine imagery is not incompatible with the God of the Bible nor with the male Jesus of Nazareth describing his love for the people of God. Finally, John 3:1–8 is analyzed as a text in which profoundly feminine, motherly imagery is used of the Spirit. To be “born again” is to be “born of the Spirit” according to Jesus’s teaching. For Pierce and Heim, this association of regeneration with birthing imagery suggests that the Spirit relates to the people of God in motherly ways.

Before offering a few enumerated points of application by way of conclusion, the authors consider some of the metaphors used by the Apostle Paul in his care for the churches at Galatia, Thessalonica, and Corinth where the apostle declares that he is in labor pains while waiting for Christ to be formed in the Galatians (Gal 4:19), that he cares for the Thessalonians as a nursing mother cares for her child (1 Thess 2:7–8), and that he gives milk to the Corinthians rather than solid food (1 Cor 3:2). Paul, then, is an example of how to inhabit the metaphors of divine motherly care in our own spiritual formation and care for others.

Critique

Pierce and Heim correctly state that God is not sexed as male or female, and they identify multiple biblical texts that undeniably describe the relation of God to his people using distinctly motherly (and thus, feminine) metaphors. Further, insofar as creatures participate analogically in the divine life, possessing as capacities of our natures what God is by nature, God’s motherly care and affection for his people should be emulated by Christians seeking to image him to the world. Putting forward the Apostle Paul as an example of what this looks like in ministry is a fitting move to which few would object. However, the essay as a whole suffers from an imprecise and inadequate account of theological language, leading to deep confusion and potentially serious error in the doctrine of God.

Metaphor and Theological Language

Is it true that “the majority of the language used of God in Scripture is metaphorical” (376), as Pierce and Heim assert? It is certainly the case that all true speech about God is analogical, but this is not the same thing as saying that all such language is metaphorical. To say that all language about God is analogical is to recognize two facts. First, God has chosen to reveal himself truly to creatures in a way that can be understood by creatures, namely through created words. Second, words predicated of God do not mean exactly the same thing in God as when predicated of creatures. Rather, words predicated of God are true of God in ways that transcend the limits of created reality. In any analogy, two things correspond to one another in ways that are similar and dissimilar. In the case of analogical language predicated of God, the two things, words and God, do not bear an exact similitude with no remainder. Rather, the fullness of God’s being transcends the capacity of meaning conveyed by finite words.

The idea that all language about God is analogical stands in stark contrast to two alternative proposals. First, the theory of analogical language stands in contrast to the theory of univocal language. If words spoken about God are univocal, then the meaning of the word discloses exactly what is true about God without remainder. The implication of this theory is that God can be comprehended intellectually (i.e., exhaustively understood) by finite creatures. Most theologians in the classical tradition have recognized that this would blur the Creator/creature distinction by reducing the being of God to the level of creatures. Second, the theory of analogical language stands in contrast to the theory of equivocal language about God. If words spoken about God are equivocal, then the meaning of a word does not disclose anything true about God. To equivocate is to express two altogether different things with the same word. To hold a theory of equivocal language about God would be to embrace a kind of functional deism in which all speech about God is merely a blind guess concerning the reality of one who is utterly unknowable. The analogical theory of theological predication affirms the fittingness of created words spoken about God to reveal truth concerning him (John 17:17) while acknowledging that the LORD’s being is ultimately beyond all comparison (Isa 46:5, 9) and his ways “inscrutable” on account of his infinite glory (Rom 11:33).

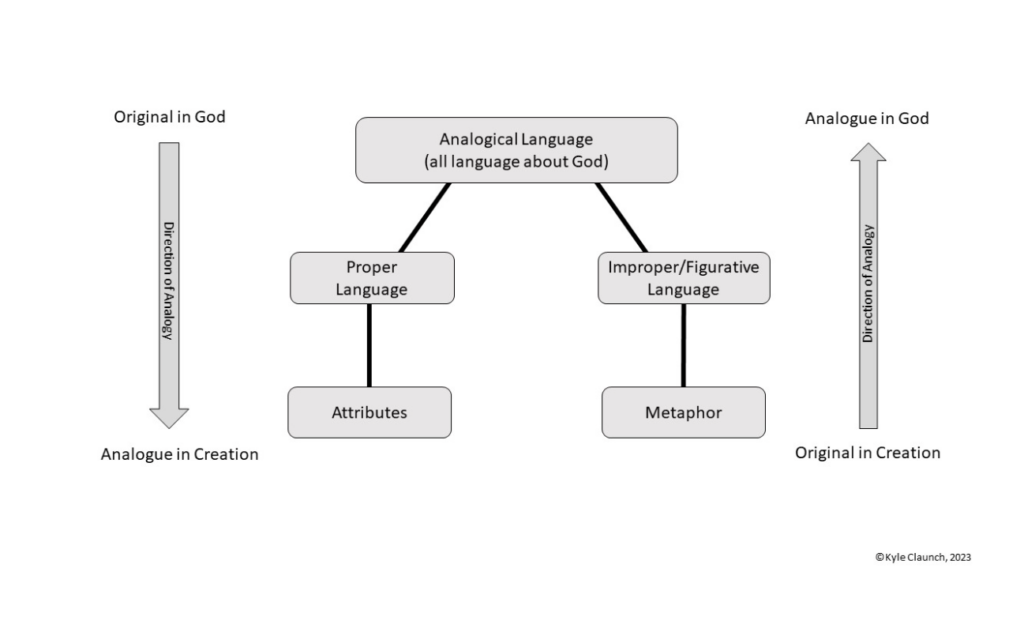

How does the notion of metaphorical language fit this account of analogical theological language? Even within the broad classical Christian commitment to analogical language, it is acknowledged that some words predicated of God are proper while other words spoken of God are improper or figurative. For example, when Scripture speaks of the LORD’s power, it speaks what is proper to God. Power is the right word to describe God’s capacity to act externally to his own being. Of course, power is predicated of God analogically, not univocally. That is, God’s power is not exactly the same thing as creaturely power. Creatures possess power as an accidental property and in varying degrees. God is power essentially, and his power is without any externally imposed limits. Still, power is attributed to God properly, not figuratively. On the other hand, something is predicated of God figuratively if that which is predicated is not proper to God’s being, but rather signifies something proper by way of the figure of speech. For example, when the prophet Isaiah says, “The LORD’s hand is not short, that it cannot save” (Isa 59:1), readers should understand that a hand and its relative size are not attributed to God properly. Rather, speaking of the LORD’s hand is a way of signifying his power (which is proper) with the imagery of a hand (which is improper). Of course, one knows that a hand is not proper to God because of the clear biblical testimony that God is an infinite, immaterial, invisible Spirit (1 Kgs 8:27; John 1:18; Rom 1:19–20; 1 Tim 1:17, 6:15–16). Predicating a hand of God is certainly metaphorical language, and as such belongs to the category of improper or figurative predication. This form of speech should be carefully distinguished from proper predication. Both kinds of predication are found abundantly in Scripture.

Another way to think about the difference between proper and improper analogical language about God is to note which direction the analogy runs. In other words, which side of the comparison is the original, and which is the analogue? Predication is proper to God when the original is in God and the analogue is in creation. Again, consider divine power. Being proper to God, power is something true of God in himself but also true of creatures in a similar yet dissimilar way. Because God is the Creator, there is an ontological priority to divine power over creaturely power. In other words, creaturely power is a derivative of divine power. Alternatively, in improper or figurative speech about God, the original is in the creation, and the analogue is applied to God. Since a hand is not proper to God, the very idea of a hand is drawn from created reality and applied to God derivatively, in that it signifies what is proper to God by terms that are improper to him.

To sum up thus far, all language about God is analogical. Under the universal category of analogical language, classical Christian theologians have always recognized that some language about God is proper while some is improper/figurative.[3] Proper language is true of God in such a way that a term applied to creatures is understood to be derivative of the original reality in God. Improper language is true of God in such a way that the term applied to God is understood to be derived from creation so that what is original to creatures signifies some truth about God by means of figures of speech. Divine attributes (such as power) classically understood, belong to the proper category while metaphors belong to the improper/figurative category (see Figure 1. “Mapping Theological Language”).

Figure 1. “Mapping Theological Language”

Against the backdrop of this overview of theological language in classical Christian theology, it becomes clear that Pierce’s and Heim’s categories are inadequate and imprecise, though they are dealing with a subject (language used to speak of God) that demands the greatest care and precision. When they claim that “the majority of the language used of God in Scripture is metaphorical,” they are failing to account for such vital distinctions in theological language as those outlined above, distinctions drawn from Scripture’s own pattern of speaking about God.

God the Father: Proper or Improper Predication?

So, what does all this talk of theological language have to do with Pierce and Heim’s discussion of motherhood language for God? A great deal, it turns out. Pierce and Heim operate with the uncritical assumption that motherhood imagery and the name Father both occupy the same linguistic and theological space — metaphor. They seem to be unaware of the broader category of analogical language and the important distinction between proper and figurative language under that broader category. Their logic seems to be: because God is not biologically sexed as male, it follows that the name Father must be a metaphor for God since all created fathers are biologically sexed as male. However, this line of reasoning assumes that the name Father has creatures as its original designation. That is, it assumes the direction of the analogy runs from creation to God. However, if the direction of the analogy runs the other way, i.e., if fatherhood is somehow original to God and is spoken of creatures by way of analogical correspondence, then the name Father is proper to God, not merely a metaphorical figure of speech.

The following three observations demonstrate that the name Father is, in fact, proper to God and therefore not a metaphor. First, in Ephesians 3:14–15, Paul states explicitly that fatherhood is proper to God and that fatherhood in creation is derived from its original in God: “For this reason I bow my knees before the Father, from whom every family in heaven and on earth is named.” The word “family” in v. 15 translates the Greek word πατριὰ, which means fatherhood. It is true that this word can be a general designation for the family unit as a whole, but this extension of the meaning of the word only makes sense because of the ubiquitous recognition that it is fitting to name the family in terms of its covenantal head. Nearly all the major English translations provide some kind of marginal note pointing out the semantic overlap of the word “father” in v. 14 (πατήρ) and the word translated “family” in v. 15 (πατριὰ). The ESV even suggests “fatherhood” as an alternate translation. Paul is stating here that fatherhood in creation (“in heaven and earth”) derives its name from God the Father, to whom Paul and all faithful Christians bow the knee. Dutch Reformed Theologian Herman Bavinck captures the sense well:

This name “Father,” accordingly, is not a metaphor derived from the earth and attributed to God. Exactly the opposite is true: fatherhood on earth is but a distant and vague reflection of the fatherhood of God (Eph. 3:14-15). God is Father in the true and complete sense of the term… He is solely, purely, and totally Father. He is Father alone; he is Father by nature and Father eternally, without beginning or end.[4]

Note that Bavinck is recognizing the direction in which the metaphor runs as distinguishing how one should understand the name or attribution. “Father,” he says, is not “derived from the earth and attributed to God.” The opposite is true. The analogue runs from God to creation. Centuries before Bavinck, Thomas Aquinas cited Ephesians 3:14–15 as a prime example of the distinction between proper and metaphorical predication. Because the name Father has its origin in God and its analogue in creation, it is therefore a proper designation for God rather than a metaphorical one.[5]

Second, the classic Trinitarian doctrine of the eternal generation of the Son gives the theological ground for saying that the name Father is proper to God. Before God created the heavens and the earth, before any created father ever had a child, the one true and living God existed perfectly, simply, and immutably as three persons in eternal relation. The first person of the undivided Godhead is named Father, not by way of metaphorical association with created fathers, but by way of his eternal relation to the second person of the Godhead, who is named Son. The Son of God is “the only begotten God, who is in the bosom of the Father” (John 1:18). Scripture speaks consistently of the Father-Son relation in God as an eternal relation that transcends all categories of created time and space. This consistency is matched by the language of classical Christian theology throughout all centuries. Fatherhood is predicated properly of the eternal first person of the Trinity in relation to the second person long before it is ever predicated of a creature. The original is in God; the analogue is in creation.[6]

Third, the fact that God is not male in no way undermines the reality that fatherhood is proper to God. This is where the category of analogical language is so important. Though fatherhood is proper to God, it is still analogical. There is similarity in the signification of the word to God and creatures, and also dissimilarity. While the nuances of similarity and dissimilarity would take us far beyond the scope of this essay and deep into the glorious mysteries of Trinitarian theology, a couple of points of clarification will still be helpful. To be a human father is to be the source of life to another human person. This is a point of limited similarity in that God the Father is the source of the eternal and uncreated divine life of God the Son (see John 5:26).[7] To be a human father also involves a biological male in a sexual relationship with a biological female. This is a point of profound dissimilarity at many levels, not the least of which is the fact that the biological/sexual category of maleness (and femaleness) does not apply to God, who is an infinite, invisible, incorporeal Spirit. Thus, male sexuality is a reality of creaturely fatherhood but not a reality of divine fatherhood, from whom all fatherhood in heaven and on earth derives its name.[8] In short, given the basic framework of analogical language, God’s non-sexual nature does not warrant the conclusion that the name Father is a mere metaphor.

Motherly Metaphors for God

Pierce and Heim rightly identify a number of biblical texts in which distinctly motherly imagery is used to describe God’s covenantal relation to his people. Because they fail, however, to articulate or even assume appropriate categories of theological language, they believe that such metaphorical imagery legitimizes the use of other names to complement the name “Father,” such as “mother” or “parent.” But Pierce and Heim’s understanding of theological language cannot account for the fact that Scripture explicitly and frequently names God as Father (in addition to fatherly imagery used to describe him) while it never names him as Mother (in spite of some motherly imagery used to describe him). A classical account of theological language, like the one given above, accounts for this phenomenon of the biblical text quite well. God is never explicitly named Mother because such imagery only describes him figuratively. God is explicitly named Father because this designation properly names God in a non-figurative way. The way Pierce and Heim appeal to Paul’s use of motherly metaphors to describe his love for those under his care actually illustrates this principle quite well. While Paul uses decidedly feminine/motherly metaphors in some texts, it does not follow that Paul could ever be called a woman — or a mother. This is because the feminine metaphors only signify truth about Paul’s love for the churches improperly by a figure of speech.

The essay by Pierce and Heim in the third edition of Discovering Biblical Equality replaces R. K. McGregor Wright’s essay, “God, Metaphor, and Gender: Is the God of the Bible a Male Deity?” in the second edition.[9] Wright sets out to argue definitively that God is not properly a male deity. In the course of his essay, Wright asks whether the personal Trinitarian names, Father and Son, suggest that God is male. He answers in the negative because, just like the names Lamb, Branch, Shepherd, and Lion are metaphorical, so the name Father is metaphorical when spoken of God (295). Because Father is a metaphorical name, one should not conclude that God is male. Interestingly, Wright goes on to say that the name Father is not interchangeable with nor complementary to alternatives, such as Mother or Parent. On this point, Wright disagrees with Pierce and Heim (and many other egalitarians). Wright’s insistence, however, that the name Father is merely metaphorical seems to undermine his claim. Since images of motherhood are clearly used of God metaphorically, it seems to follow that God can be called Mother as well as Father if Father is only a metaphorical name. Wright’s concern is to let Scripture speak for itself. Since Scripture never explicitly names God as Mother, neither should we. But Wright’s inattention to proper theological categories leaves him without explanation as to why Scripture speaks of God explicitly as Father but not as Mother.

Conclusion

Pierce and Heim rightly observe that Scripture describes the LORD’s relation to his covenant people in metaphorical terms of motherhood. Furthermore, there are appropriate ways for God’s people to imitate his tender care as they love and care for one another, a pattern exemplified by the Apostle Paul, who describes his care for the Galatian and Thessalonian churches using the imagery of motherhood. Unfortunately, Pierce and Heim give inadequate attention to the nature of created language and its legitimacy and limitations when spoken of God. By subsuming all (or nearly all) speech about God under the heading of metaphor, they have left no space for analogical predication of God that is proper as opposed to merely figurative or metaphorical. Thus, they have reduced all descriptions of God to the level of imagery drawn principally from creation and have not accounted for descriptions of creation that have their origin in God. The implications of this imprecision are theologically significant, minimizing the consistent biblical testimony to the proper name of the first person of the Trinity in relation to the second. Additionally, such imprecision undermines believers’ confidence that we can speak anything properly of God, or indeed that God can speak anything properly concerning himself to creatures, however inexhaustive such speech may be. Therefore, the chapter by Pierce and Heim does not help readers “understand better and experience more fully” the triune God (373). Rather, the lack of theological precision in matters of great weight and consequence leads to a collapsing of important distinctions and thus diminishes understanding rather than deepening it.

Kyle D. Claunch is Associate Professor of Christian Theology at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary where he has served since 2017. He and his wife Ashley live with their six children in Louisville, KY. He has more than twenty years of experience in pastoral ministry and is a member of Kenwood Baptist Church.

[1] The logic here is very similar to the more expansive treatment of these issues in Amy Peeler, Women and the Gender of God (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2022). She writes, “To think of God as beyond gender in the sense that God encompasses aspects of both genders, that God is Parent or Mother and not only Father, helps to work against the ‘phallacy’ that God is male” (17).

[2] I use the word “attempting” to register my hesitation with the designation, “Yahweh, the covenant God of Israel” in reference to God the Father exclusively. YHWH is a proper name for the triune God and can thus name all three persons. The NT demonstrates this by associating the name YHWH with all three divine persons (see, e.g., 2 Cor 3:15–18 [of the Spirit], Heb 1:10–12 [citing Ps 102:25–26, of the Son], Mt 22:43–45 [citing Ps 110:1 in which Jesus identifies YHWH with the Father]).

[3] Thomas Aquinas gives a careful treatment of the nature of analogical language, contrasting it with univocal and equivocal language in the Summa Theologiae (ST) I, q. 13, a. 5. Under the broad heading of analogical predication, Thomas recognizes a very clear distinction between proper and improper language, locating metaphor explicitly on the improper side, a distinction essential to the proper interpretation of Scripture (ST I, q. 1, a. 10 and q. 13, a. 6; see also Galatians Commentary, c. 4, l. 7). It can be argued that Thomas’s conceptual terminology and clear distinctions represent a general consensus of Christian tradition up to his time. It is beyond dispute that this theory of theological language was a mainstay of later theologians, both Roman Catholic and Protestant. On the Protestant side, see John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, 1.13.1; Francis Turretin, Institutes of Elenctic Theology, Vol. 1, 187–91; Richard Muller, Post-Reformation Reformed Dogmatics, The Rise and Development of Reformed Orthodoxy, ca. 1520 to ca. 1725, Vol. III: The Divine Essence and Attributes, 195–201; and Herman Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics, Vol II: God and Creation, 107–110.

[4] Reformed Dogmatics, II: 307–8.

[5] ST I, q. 13, a. 6.

[6] This brief discussion has focused on the name Father as a proper personal name in that it is proper to only one person of the Trinity and names his relation to another divine person. It should be noted, however, in Scripture the name Father is predicated of God essentially as well. That is, God is named Father in such a way that the name applies fittingly to all three persons because it is predicated of the divine being and names God in relation to creation. Even in this way, the name is still proper to God, not merely metaphorical, but a full discussion of this will have to await a future article.

[7] Of course, even with a point of similarity, the similarity is not exact. Human fatherhood involves chronology (the father exists before the child), procreation (the father is not the sole source of the child), and duplication (the production of another human nature) whereas God the Father generates the Son eternally (no before and after), exclusively (no partnership with another being), and identically (the Son’s nature is numerically the same as the Father’s, even though the Son is God from the Father).

[8] More needs to be said about the proper fatherhood of God, especially what makes the eternal relation between the first and second persons of the Trinity a Father-Son relation as opposed to a Mother-Daughter relation. Beyond this, the consistent Scriptural use of masculine pronouns for God needs to be discussed. These questions are beyond the scope of this review essay and will also have to await a later article.

[9] R. K. McGregor Wright, “God, Metaphor, and Gender: Is the God of the Bible a Male Deity?” in Discovering Biblical Equality: Complementarity Without Hierarchy, 2nd Ed, ed. Ronald W. Pierce and Rebecca Merrill Groothuis (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2005), 287–300.

You, too, can help support the ministry of CBMW. We are a non-profit organization that is fully-funded by individual gifts and ministry partnerships. Your contribution will go directly toward the production of more gospel-centered, church-equipping resources.