Editor’s note: The following essay appears in the Spring 2020 issue of Eikon.

When I took what was called Church History I and Church History II in 1974–1975, the normal year-long survey of church history given to first-year theology students, I do not recall hearing anything about clothing and fashion. Yes, there was much about the “big” names in church history — Athanasius and Augustine, Anselm and Aquinas, Luther and Calvin — but nothing about clothing. After all, surely God is not really interested in what we wear and what we put on our bodies? And even if he was, how does that have any bearing on the history of the church?

Now, the answer to that first question is an easy one. Yes, ever since God clothed our first parents after the Fall, he has been interested in what we use to cover our nakedness (see, for example, 1 Tim. 2:9). The answer to the second question is more complex, as shown by the following mini-history of the color purple.

Making ancient Tyrian purple

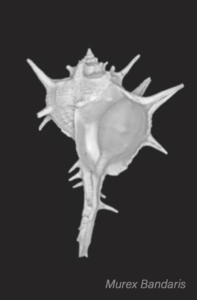

Purple was a highly prized color in the Old Testament world of the ancient Near East, where it was associated with royalty and prestige and power. In part, purple was so highly valued because obtaining it entailed monumental difficulties. According to the Roman scientist Pliny the Elder, who died in the eruption of Vesuvius in A.D. 79, the best purple dye in the ancient Near East was manufactured at the Phoenician city of Tyre. The raw material out of which this dye was manufactured was obtained from the glandular secretion — or tears, as the Christian commentator Isidore of Seville poetically put it — of a carnivorous sea snail, which contemporary science knows as the Murex bandaris. Somewhere around twelve thousand of these snails had to be harvested from the sea to produce merely 0.05 of an ounce of dye. A foul stench emanated from the Phoenician factories manufacturing the dye, which were understandably placed on the outskirts of the city. Tyrian purple, as it was known, was literally worth more than its weight in gold, and purple-dyed fabrics commanded exorbitant prices. As Pliny noted of ancient fashion, “it adds radiance to every garment,” and this led to what he called a “frantic passion for purple” among the upper and middle classes of his world.

Purple was a highly prized color in the Old Testament world of the ancient Near East, where it was associated with royalty and prestige and power. In part, purple was so highly valued because obtaining it entailed monumental difficulties. According to the Roman scientist Pliny the Elder, who died in the eruption of Vesuvius in A.D. 79, the best purple dye in the ancient Near East was manufactured at the Phoenician city of Tyre. The raw material out of which this dye was manufactured was obtained from the glandular secretion — or tears, as the Christian commentator Isidore of Seville poetically put it — of a carnivorous sea snail, which contemporary science knows as the Murex bandaris. Somewhere around twelve thousand of these snails had to be harvested from the sea to produce merely 0.05 of an ounce of dye. A foul stench emanated from the Phoenician factories manufacturing the dye, which were understandably placed on the outskirts of the city. Tyrian purple, as it was known, was literally worth more than its weight in gold, and purple-dyed fabrics commanded exorbitant prices. As Pliny noted of ancient fashion, “it adds radiance to every garment,” and this led to what he called a “frantic passion for purple” among the upper and middle classes of his world.

The Christian seller of purple

Now, jump forward to one highly significant mention of this color of clothing in the New Testament. In Luke’s Book of Acts, we read that when the Apostle Paul came to the city of Philippi in A.D. 49, he met a woman named Lydia, who was originally from the city of Thyatira in the Roman province of Asia (modern-day Turkey). Ethnically, she was Greek, but she had come to believe that the Jewish Old Testament contained the truth about God and the world, and thus she regularly met with a number of sincere Jewish women to pray and worship (Acts 16:14–15).

We are also told by Luke that she was “a dealer in purple” (v. 14), which meant that she either sold the dye, or, more likely, sold purple-dyed clothing. Either way, she would have been a woman of wealth and substance. Her regeneration by the Holy Spirit — “the Lord opened her heart” (v. 14) — led to her baptism and to her encouraging Paul to use her home as a base of mission in the city of Philippi.

If one reads through the Book of Acts, it is apparent that when Paul went with the gospel to a new city, a key part of his mission strategy was to find a place where the churches that were founded through the preaching of the gospel could meet for distinctively Christian worship and fellowship. So it was that in Philippi, the Lord used the wealth that Lydia had obtained by the selling of purple clothing to rich and elite women — women who had a “frantic passion for purple” — to serve Paul’s preaching and teaching about the Lord Christ.

The God who so made the Murex bandaris that its glands contained the base for purple appears to have had a greater purpose in mind than the making of a snail, wondrous though that be!

Michael A. G. Haykin is chair and professor of church history at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary and Director of the Andrew Fuller Center for Baptist Studies at Southern.

You, too, can help support the ministry of CBMW. We are a non-profit organization that is fully-funded by individual gifts and ministry partnerships. Your contribution will go directly toward the production of more gospel-centered, church-equipping resources.