Through the ages, similarities and differences in the intellectual and ethical development of men and women have been examined and debated. Author and educator Elizabeth Hayes writes:

Women’s potentially distinctive characteristics as learners have been a topic of interest to scholars, educators, and women themselves for centuries. Noted Western (male) philosophers, ranging from Plato to Rousseau, questioned whether women could learn at all, or could at least engage in the kind of rational thought typically associated with “higher” learning. [1]

In the last seventy years, this debate has continued as empirical studies have assessed epistemological development. Many of these foundational studies have either ignored gender or presupposed men and women to be completely different in their epistemological development. Despite this divide in approach, research actually demonstrates what one might expect from a biblical perspective.

Biblically, similarity between the sexes with different patterns and perspectives is expected. In Scripture, there are not two separate views of knowledge — one for men and one for women. Men and women are created in the image of God (Gen. 1:27). Both are fallen (Rom. 3:10–12, 23). Both are redeemed in the same way, by the same Savior, believing the same gospel and the same truths (John 14:6; Rom. 10:9; Acts 16:31; Col. 1:13–14; Eph. 1:7; 1 Tim. 2:6; Heb. 9:12; Rom. 3:23–25). In Scripture, men and women are addressed separately in certain passages with some distinctions (1 Tim. 2; Col. 3; Eph. 5; 1 Cor. 14), but the vast majority of scriptural commands apply to both men and women.

Empirical research has shown similarity in male and female epistemological development, while also acknowledging differences. This is seen through an examination of the foundational studies in the field, the similarities in their overarching patterns of development, and the different patterns and perspectives revealed between men and women.

Why Spend Time on This Issue?

These patterns are important for understanding both female and male learners and their growth and experiences as such. Hayes has also written, “It can be tempting to simply ignore gender, perhaps in the name of treating each person as a unique individual. Ignoring gender can make us blind to the significant impact that it can have on our learners.”[2]

As believers, our need to consider this topic goes further. Knowing is ethical, so considering the epistemological growth of both sexes is worth consideration because it values all humans and is a study of God’s creative work. Though men and women have the same ethical, moral, and spiritual responsibilities before God in the use of their minds, that God created women differently than men means it is appropriate to explore these differences.

Foundational Studies in Epistemological Development

While many studies in the field could be used to demonstrate this similarity with different patterns and perspectives, three foundational studies will be used.

William Perry. In 1970, William Perry laid out a scheme of epistemological development in his book, Forms of Intellectual and Ethical Development in the College Years. This work resulted from the qualitative, longitudinal study Perry did at Harvard in the 1950s and 60s on undergraduate males. His scheme shows a progression of nine positions grouped into four stages: dualism, multiplicity, contextual relativism, and commitment within relativism. Perry’s scheme has continued to be verified and used to measure epistemological development.

Belenky et al. Shortly after Perry’s work was published, Mary Field Belenky, Blythe McVicker Clinchy, Nancy Rule Goldberger, and Jill Mattuck Tarule raised the issue of women’s epistemological development being assessed according to male development patterns. Their findings from their study, conducted by women on women, were published in their book Women’s Ways of Knowing.

Their study included females who were college students, recent graduates, or students in “the invisible college,” which they defined as institutions that helped women in need. Despite varying greatly from Perry’s pool of Ivy League men, their research did not reveal a new structure. They observed different patterns and perspectives that were attributed to gender, but the categories, though differently named, demonstrated the same progression of development. Their findings had five major categories: silence, received knowledge, subjective knowledge, procedural knowledge, and constructed knowledge.

Baxter Magolda. Marcia Baxter Magolda also contributed to the research on epistemological gender differences with a study that followed students from their first year of college through their first year after graduation. This study compared both men and women in one study, whereas the studies by Belenky et al. and Perry were decades apart and studied different populations. Baxter Magolda’s findings were published in her book, Knowing and Reasoning in College: Gender-Related Patterns in Students’ Intellectual Development. She recognized there were different patterns that men and women tended to fall into, but one main scheme of development for both. Her stages of knowing were absolute knowing, transitional knowing, independent knowing, and contextual knowing.

Study Similarities

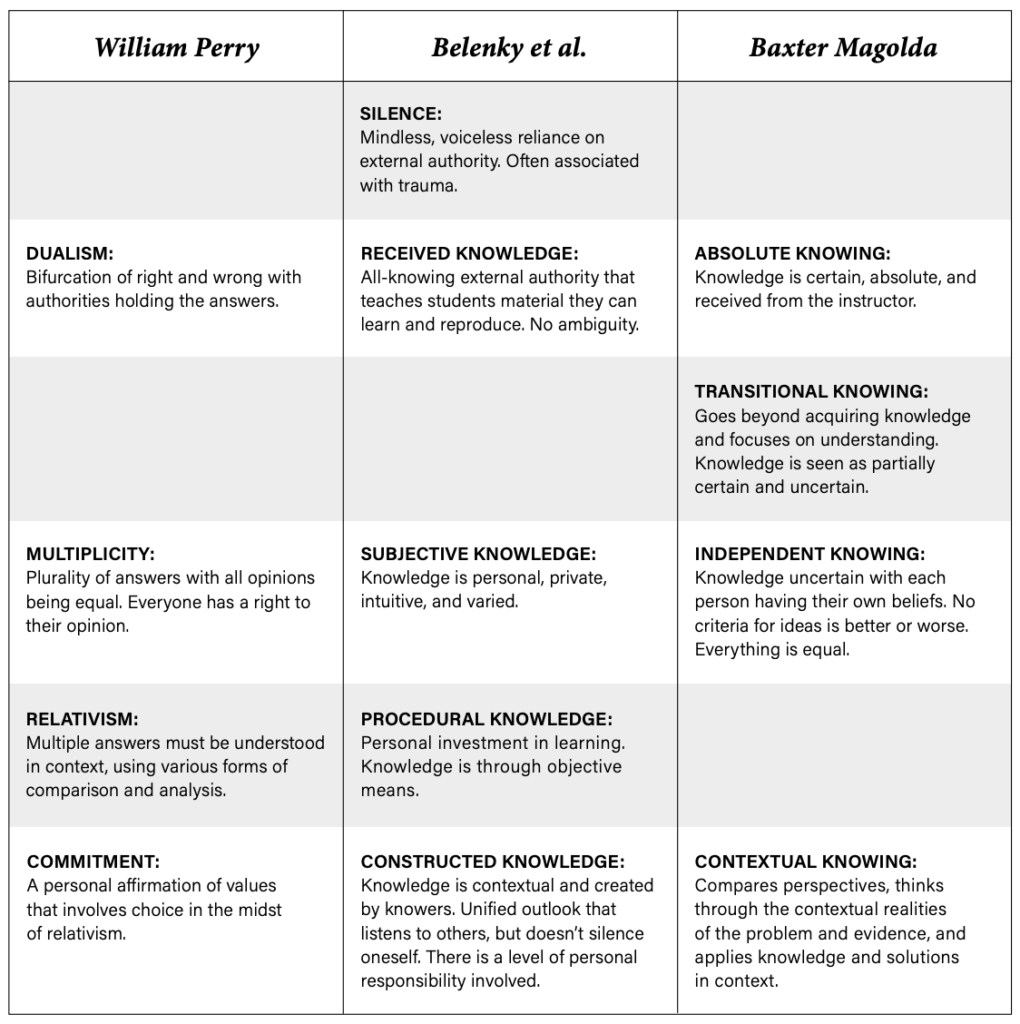

While the different studies had slight variations, overall the arc of knowledge development is the same. This arc moves from the learner believing that every question has a black and white answer with authorities knowing everything, to understanding that authorities can disagree. This leads to a cacophony of possible truth, where the learner believes all answers are equal and each individual can make a personal decision. As the learner continues to develop, however, he or she realizes that some assertions are better supported than others. Possible answers must be examined and understood in context. Finally, the learner progresses to understand that knowing goes beyond a list of facts and examination, but there is a personal responsibility to affirm values. Knowing is ethical, and the knower bears a responsibility. These parallels can be seen in the chart below with descriptions of each of their stages.

The three studies categorized their findings differently, but overall the same arc of knowledge development remains. Men and women bring different patterns and perspectives, but are not altogether different in their ethical and intellectual development.

Study Differences

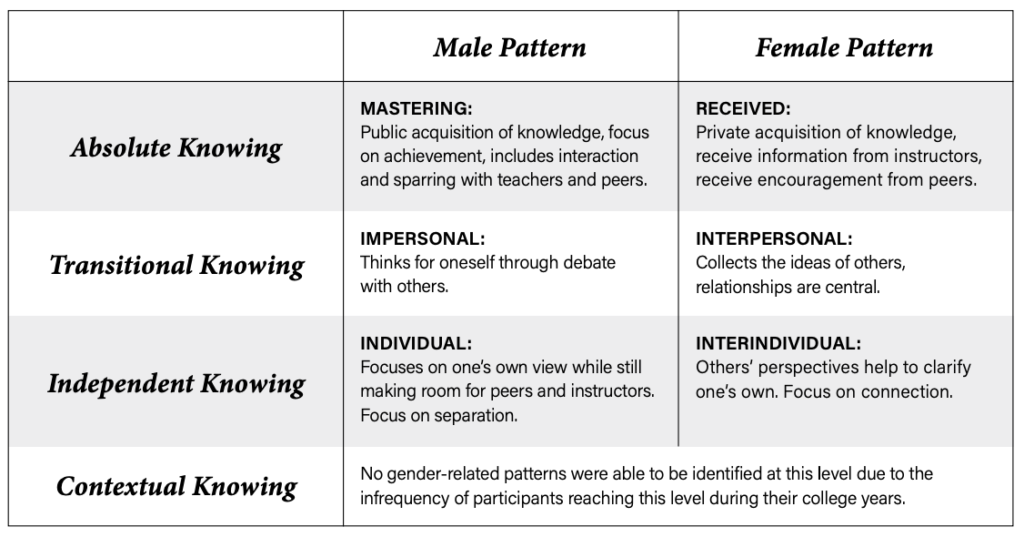

Baxter Magolda’s study is helpful in viewing some of these patterns and perspectives as she examined men and women from the same context in the same study. Her study resulted in four different ways of knowing, with corresponding gender-related patterns in the first three. While women and men did not always fall into their gender-related pattern, the following patterns were observed:

While there were not enough data to establish gender patterns for contextual knowing, Baxter Magolda speculated at the possibility of gender patterns converging in contextual knowing:

Because contextual knowers integrated thinking for themselves with genuine consideration of others’ views, it is possible that the gender-related patterns of earlier ways of knowing converged in contextual knowing. For example, receiving-, interpersonal-, and interindividual pattern knowers’ focus on connection to others is a central feature of contextual knowing when integrating other valid views. Mastery-, impersonal-, and individual-pattern students’ individual approach is also a basic feature of contextual knowing, because students are ultimately responsible for their own judgments and constructed perspectives.[3]

As an example of this convergence, Baxter Magolda describes one of her male students demonstrating more empathy over the years and one of her female students enjoying more debate over the years.

In Baxter Magolda’s gender-related patterns, Belenky et al.’s work, and in other studies related to women’s development, several themes emerged, including voice, relationship, and connectedness, with an overarching tenor of care.

Voice. Women in the studies were less likely than men to speak up, but voice in the studies represented an increased movement from echoing the voices of others to engaging ideas and developing one’s own voice. Baxter Magolda relates this hesitancy to speak to women’s tendency toward relationship, saying, “Women’s interest in getting to know others and supporting each other matches earlier research suggesting women see themselves as connected to others. The men expressed more interest in active involvement in looking for answers, argument and quizzing each other.”[4] She suggests that men state their opinions, while women refrain from doing so out of a desire not to separate themselves from those around them. When women do share their opinion, “it is with qualification of the limits of the opinion to personal experience.”[5]

Relationship. Baxter Magolda’s gender-related patterns show the added importance of relationship for women when it comes to knowing. In transitional knowing, the pattern more characteristic of women relies on peers more than the pattern characteristic of men, which is individually focused. In independent knowing, both males and females value their own opinions and those of others, but women tend toward more collaboration in that process. One of the male participants in the study recognized this propensity, saying, “You need that other gender’s input. I feel more comfortable talking with women sometimes because of that building-towards-community attitude . . . . You can tell they’re listening and care.”[6] Relationships were a part of men’s development as well, but “for women, confirmation and community are prerequisites rather than consequences of development.”[7]

Connectedness. Connectedness is the idea that the knower and what is known are in relationship. Connectedness does not consider something from an independent viewpoint, but is empathetic, trying to understand. Separate knowing considers things in a disassociated manner, excluding emotion, and starting from a vantage point of doubt as an adversary. Connected knowing sees personality and affect as adding to a perception. It is more reluctant to play the doubting game. Connected knowing still examines and thinks objectively, but as an ally, not an adversary.

Care. These themes of voice, relationship, and connectedness all have aspects of care displayed. There is thoughtfulness and understanding. This theme of care in women’s epistemological development — and the term “care” — is common throughout the literature in the field. Care was absent from epistemological studies that exclusively included men, but it is very present when women are included.

Alike, but Different

While foundational studies in epistemological development have often either overlooked or highly emphasized gender, setting up an alternate scheme for development, the studies in the end reveal the similarities between men’s and women’s epistemological development. Yes, there are different patterns and perspectives that are important to explore — there are different elements that emerge when women are included — but overall epistemological development is not bifurcated, but unified. This should lead us all the more to explore created differences and similarities to better understand intellectual and ethical maturity, to better understand learners, and to better understand humans made in the image of God.

Jenn Kintner holds a Doctorate of Education from The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. Prior to her current role at The Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission (ERLC), she spent ten years working in higher education.

[1]Elisabeth R. Hayes, “A New Look at Women’s Learning,” New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education 2001, no. 89 (2001), 35.

[2]Elisabeth R. Hayes, “A New Look at Women’s Learning,” New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education 89 (2001), 40.

[3]Marcia Baxter Magolda, Knowing and Reasoning in College: Gender-Related Patterns in Students’ Intellectual Development (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1992), 189. Baxter Magolda is not the only one to speculate that gender-related patterns start to converge at more advanced levels of knowing. Both Gilligan and Belenky et al. hint at this as well. Gilligan writes, “Thus, starting from very different points, from the different ideologies of justice and care, the men and women in the study come, in the course of becoming adult, to a greater understanding of both points of view and thus to a greater convergence in judgment. Recognizing the dual contexts of justice and care, they realize that judgment depends on the way in which the problem is framed.” Carol Gilligan, In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982), 167.

[4]Marcia B. Baxter Magolda, “Gender Differences in Cognitive Development” (paper presented at the American Educational Research Association Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, April 22, 1987), 19.

[5]Baxter Magolda, “Gender Differences in Cognitive Development,” 11.

[6]Baxter Magolda, Knowing and Reasoning in College, 65.

[7]Mary Field Belenky, et al., Women’s Ways of Knowing: The Development of Self, Voice, and Mind (New York: Basic, 1997), 194.

You, too, can help support the ministry of CBMW. We are a non-profit organization that is fully-funded by individual gifts and ministry partnerships. Your contribution will go directly toward the production of more gospel-centered, church-equipping resources.