Editor’s note: The following essay appears in the Spring 2022 issue of Eikon.

Introduction

With increasing pressure from the culture to revise the traditional moral disapproval of same-sex relations, evangelicals are wrestling with how the church ought to treat same-sex attracted Christians. A shift toward greater openness is taking place among some evangelical churches committed to the authority of Scripture as the only infallible rule of doctrine and life. A small but growing number of evangelical pastors and congregations have shifted from holding that same-sex activity is irreconcilable with commitment to Christ to allowing committed same-sex relationships within their membership.[1]

It remains to be seen how these evangelicals will answer further questions, such as whether same-sex relationships can be blessed as a “marriage” by the church and whether such individuals are eligible for ordained office in the church. Progressive evangelical churches could accept them as members, but hold the line there and reject gay ordination and same-sex wedding ceremonies. Presumably, if they wish to remain Bible-believing evangelicals, they would still want to maintain that same-sex relationships fall short of God’s creation ideal for sexuality and cannot be called “marriage” as the Bible defines it — a male-female one-flesh union. They would thus be pastorally accommodating same-sex relationships rather than treating them as true marriages fully blessed by God and endorsed by the church.

The best example of an evangelical holding this position is Lewis B. Smedes (1921–2002), who was a minister in the Christian Reformed Church and a professor of ethics at Fuller Theological Seminary. In Sex for Christians (1976), Smedes outlined a three-step discernment process for the same-sex attracted Christian. Step one is self-knowledge, meaning that the homosexual person must face the abnormality of having a same-sex orientation and refuse to blame themselves for this unchosen condition. Step two is hope — they should believe that change (from being homosexual to being heterosexual) is possible and seek it. But for those who have sought change and could not find it, there is a third step, which Smedes labels “accommodation.” The third step has two sub-steps. Step 3a is to consider whether the homosexual person is called to celibacy. For those who cannot manage celibacy, we come finally to Step 3b, and that is what Smedes calls “optimum homosexual morality,” which he describes as follows:

What morality is left for the homosexual who finally . . . can manage neither change nor celibacy? He ought, in this tragic situation, to develop the best ethical conditions in which to live out his sexual life . . . . To develop a morality for the homosexual life is not to accept homosexual practices as morally commendable. It is, however, to recognize that the optimum moral life within a deplorable situation is preferable to a life of sexual chaos . . . Here, as in few other situations, the church is called on to set creative compassion in the vanguard of moral law . . . It cannot fulfill its ministry simply by demanding chastity . . . . The agonizing question that faces pastors of homosexual people comes when the homosexual has found it impossible to be celibate. What does the church do? Does it drop its compassionate embrace and send him on his reprobate way? . . . . Or does it, in the face of a life unacceptable to the church, quietly urge the optimum moral life within his sexually abnormal practice?[2]

Smedes recognizes that each church community will have to answer these questions for itself, but he himself leans toward urging the optimum moral life within sexually abnormal practice. He is more explicit in “Second Thoughts” in the 1994 revised edition of Sex for Christians. While continuing to affirm that “the Creator intended the human family to flourish through heterosexual love,” Smedes nonetheless believes that “God prefers homosexual people to live in committed and faithful monogamous relationships when they cannot change their condition and do not have the gift to be celibate.”[3]

This is the pastoral accommodation approach to homosexuality. Accomodation is not affirmation. Those adopting this position do not endorse homosexuality as positively good and intended by the Creator. They acknowledge that homosexuality is a result of the fall. They also generally refrain from speaking of “same-sex marriage.” They want the church to uphold the creation ordinance of opposite-sex marriage and the church’s traditional sexual ethic. But they also want the church to be pastorally sensitive, adopting a compassionate embrace rather than driving such people away from the church.

As attractive as such an approach may be to some, it runs up against a major hurdle: the apparent teaching of Paul in 1 Corinthians 6:9–11:

Or do you not know that the unrighteous will not inherit the kingdom of God? Do not be deceived: neither the sexually immoral, nor idolaters, nor adulterers, nor men who practice homosexuality, nor thieves, nor the greedy, nor drunkards, nor revilers, nor swindlers will inherit the kingdom of God. And such were some of you. But you were washed, you were sanctified, you were justified in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ and by the Spirit of our God. (ESV, emphasis added)[4]

Verses 9–10 are in the literary form of a vice list,[5] and one of the vices is the practice of homosexuality. Paul’s teaching seems fairly clear: those who persistently practice these vices, including the practice of homosexuality, are the unrighteous, and the unrighteous are excluded from the kingdom of God. Paul states that among the membership of the church of Corinth there were those who had formerly been such sexually immoral people, but he says they are not such any more. They had repented and received cleansing and forgiveness in Christ. The implication is that such people would be excluded as long as they do not repent. This would seem to rule out pastoral accommodation of same-sex relationships. The purpose of this article is to engage in a careful exegesis of this paragraph and its immediate context (1 Cor 5–6) to see if that is in fact Paul’s teaching.

The Context: 1 Corinthians 1–6

Paul begins his first letter to the Corinthians by addressing factionalism (chs. 1–4). The church was divided based on different understandings of “wisdom” (σοφία). David Garland convincingly argues that some of the Corinthians had imbibed values from the surrounding culture that were antithetical to the message of the cross — striving for power, honor, prestige, status, and fleshly wisdom. In response, Paul shows how the wisdom of the cross annihilates all pride and leaves no room for factions based on following one supposed wise man over another.[6]

Then in chapters 5–6, Paul turns to the topic of church discipline and rebukes the Corinthian Christians for their failure to act as wise men who judge those inside the church. They claim to be wise and yet their toleration of grave immorality in their midst shows the hollowness of their claim. Already in 1 Corinthians 4, Paul sees the Corinthians as being “puffed up” with spiritual pride (4:6, 18–19). When he turns to the discussion of the church’s toleration of an egregious case of incest (a Christian man in a sexual relationship with his father’s wife), Paul uses this obvious moral failure on the part of the church to puncture their pride, “And you are arrogant (πεφυσιωμένοι)! Ought you not rather to mourn?” (5:2), and then again a few verses later, “Your boasting (καύχημα) is not good” (5:6).

First Corinthians 5:1–6:20 forms a unit that can be subdivided as follows:

The theme of sexual immorality is clearly found in sections a, c, and d. Commentators have puzzled over how section b (Paul’s rebuke of brothers suing each other in the secular courts) fits in the surrounding context. Some have suggested that the lawsuits had to do with sexual offenses, perhaps related directly to the incest case of the previous chapter. But this is unlikely, given that Paul thinks those bringing the lawsuits should simply accept being wronged (6:7), counsel he would be unlikely to give if the lawsuits concerned sexual offenses. How, then, does this section on lawsuits fit in? Garland argues that in these two chapters Paul cites three appalling moral failures — the church’s toleration of an egregious case of incest; brothers taking each other to court; and Christians visiting prostitutes — to puncture the Corinthians’ pride in their supposed wisdom and spiritual superiority.[7]

Lexical Semantics of Select Items in the Vice List (1 Cor 6:9–10)

We have looked briefly at the context. We now turn to examine select items in the vice list. The vice list contains ten sins, but most of them (idolaters, adulterers, thieves, the greedy, drunkards, revilers, swindlers) are not very controversial and not directly relevant for this article. However, the lexical semantics of three of the sin words — πόρνοι, μαλακοί, and ἀρσενοκοῖται — demands particular attention if we are to answer the theological question motivating this article.

πόρνος, ὁ: one who practices sexual immorality, fornicator[8]

It is believed that the words in the πορν- group were derived from the verb πέρνημι, which means “to sell, to traffic,” and which was particularly used in reference to slaves, both male and female, who were often sold to be used for sex.[9] In extra-biblical Greek, this word-group had a narrow application: a πόρνη was a female prostitute, πορνεύω was the verb for prostituting oneself, the abstract noun πορνεία denoted the practice of prostitution, a πορνεῖον was a brothel, πορνογενής meant to be born of a prostitute, and so on.[10]

In the Septuagint, πορν- terms were used to render the Hebrew verb זָנָה (“have illicit intercourse”) and its cognates, זוֹנָה (“prostitute”), תַזְנוּת (“prostitution, promiscuity”), זְנוּנִים (“prostitution”), and זְנוּת (“prostitution”). In addition to the use of such terms to refer to sexual immorality and prostitution, the terms were applied metaphorically to Israel’s spiritual unfaithfulness, which the prophets deemed a whoring after gods other than Israel’s true spiritual husband, YHWH. Kyle Harper makes an important observation about how this metaphorical application influenced the gender dynamics of the term:

The metaphorical sense of זנה as idolatry would decisively influence the development of Greek πορνεία. The metaphorical meaning allowed spiritual fornication to be used with acts of male commission. This semantic extension reversed the gender dynamics that are inherent in the primary sense of זנה. In Hosea we first see men committing fornication, albeit of the religious variety (Hos 4:18; cf. Num 25:1; Jer 13:27; Ezek 43:7-9). In Second Temple Judaism, this reversal would feed back into the sexual sense of the term, so that sexual fornication became an act that men could commit.[11]

As a rule, the LXX used πορν- words to render the Hebrew זנה words. Although in extra-biblical Greek, πορν- referred to prostitution and therefore as primarily a female sin, in the LXX and in subsequent Greek-speaking Hellenistic Jewish literature the πορν- word-group underwent semantic expansion to cover all forms of sexual immorality (although πόρνη retained its original meaning, “prostitute”).[12] There are different kinds of πορνεία. This is supported by two locutions in the nearby context of our passage: “sexual immorality of such a kind (τοιαύτη πορνεία)” (1 Cor 5:1), implying that there are other kinds; and “because of sexual immoralities (διὰ τὰς πορνείας)” (1 Cor 7:2), which implies either multiple instances or multiple kinds of sexual immorality. In Greek-speaking Hellenistic Judaism, πορνεία is any sex outside of marriage. The term πορνεία was not restricted to heterosexual activity between two unmarried people (what we would call “fornication” today), although it certainly included it.[13] Any sexual encounter or relationship that does not occur within the holy bond of marriage can be called πορνεία, including incest (T. Reuben 1:6),[14] adultery (Sirach 23:22–23; T. Reuben 4:8; T. Joseph 3:8; cf. Matt 5:32; 19:9),[15] and same-sex relations (T. Benj. 9:1).

Focusing on Paul’s usage in 1 Corinthians 6:9, πόρνοι means those who engage in sexual immorality. It is indisputable that πορνεία in Paul does not mean “prostitution” but sexual immorality, specifically incest (5:1). A few verses later (5:9–11), Paul uses the cognate word πόρνος three times: “I wrote to you in my letter not to associate with πόρνοι — not at all meaning the πόρνοι of this world.” Paul’s usage of πόρνος is consistent with its meaning in all of its occurrences in the NT, where it uniformly means “sexually immoral person.”[16]The main lexica of New Testament Greek gloss πόρνος as “one who practices or engages in sexual immorality.”[17] This is reflected in several modern English versions, which render πόρνοι in 1 Corinthians 6:9 as “the sexually immoral” (NIV, ESV) or “sexually immoral people” (CSB).

Words based on the πορν- stem (πόρνος, πορνεία, and πορνεύω) have undergone semantic expansion in Greek-speaking Hellenistic Judaism from their narrow extra-biblical usage in secular Greek, where the words had to do with prostitution, to a much broader meaning, sexual immorality in general.[18] The term πορνεία means any illicit sex, that is, sex outside of marriage, and embraces a number of specific types of immorality.[19]

μαλακός: pertaining to being passive in a same-sex relationship

ἀρσενοκοίτης, ὁ: a male who engages in sexual activity with a person of his own sex[20]

These two words have understandably been the subject of much debate. Revisionists have put forward several alternative interpretations, arguing that the terms denote any number of things other than same-sex practice, such as “masturbation,” “male prostitution,” “economic exploitation using sex,” or “non-mutual, abusive pederasty.” All these revisionist theories have been refuted by scholars like David F. Wright and Robert Gagnon.[21] The most authoritative lexicon, BDAG, supports taking the terms as straightforward references to same-sex activity and gives no support to revisionist readings.

The adjective μαλακός has a semantic range that begins with non-sexual meanings such as “soft” in the literal sense (e.g., soft clothing, soft pillows, soft skin). Extending beyond the literal usage, the term can also mean “effeminate,” and then even beyond that “passive in same-sex relations.” In this last case, it refers to a man who by dress and makeup seeks to present as a female for the purpose of functioning as the passive partner in same-sex relations. In extra-biblical Greek, the term and its cognates refer specifically to the passive partner in a male-male sexual relationship.[22] That is clearly what Paul intends here.

The noun ἀρσενοκοίτης is of particular importance. It is transparently formed from two Greek words, ἄρσην (“male”) and κοίτη (“bed, sexual relations”), a combination that is also found in the Septuagint:

LXX Leviticus 18:22: καὶ μετὰ ἄρσενος οὐ κοιμηθήσῃ κοίτην γυναικός. “And you shall not have sexual relations with a male as with a woman” (author’s translation).

LXX Leviticus 20:13: καὶ ὃς ἂν κοιμηθῇ μετὰ ἄρσενος κοίτην γυναικός βδέλυγμα ἐποίησαν. “And whoever has sexual relations with a male as with a woman, both have committed an abomination” (author’s translation).

The rabbinic literature picks up on these two verses in Leviticus and uses the Hebrew phrases mishkav zakur(“lying of a male”) or mishkav bzakur (“lying with a male”) to refer to men having sex with men. It is thought that these rabbinic phrases influenced Greek-speaking Hellenistic Judaism which coined the term ἀρσενοκοίτης as a literal Greek rendering of the rabbinic term. Most scholars recognize that Paul almost certainly has these Leviticus verses in mind when he uses the term.[23]

In view of these strong exegetical considerations, the English Standard Version takes the terms μαλακοί and ἀρσενοκοῖται together and renders them with the phrase, “men who practice homosexuality.” The New International Version (2011) has “men who have sex with men,” and the Christian Standard Bible has “males who have sex with males.” All three versions also have a footnote explaining that the terms refer to the passive (μαλακοί) and active (ἀρσενοκοῖται) partners in homosexual acts.[24]

It may be asked if Paul’s teaching in our text is intended to condemn only male homosexual practice, e.g., leaving women who have sex with women in the clear. There are two compelling reasons to answer negatively. First, in our text, Paul begins with “the sexually immoral” (πόρνοι) as a broad category of those excluded from the kingdom, and as we have seen, this includes any sex outside of marriage. After giving the broad category, “the sexually immoral,” he adds two specific types of sexually immoral persons — adulterers and men who have sex with men.[25] These are representative but not exhaustive. Second, in Romans 1:26–27, the apostle makes clear that same-sex relations are “dishonorable passions” (πάθη ἀτιμίας), whether they are of the male or the female variety.

“Do Not Be Deceived”

Taking Paul’s words at face value, it would seem that those who engage in the practice of homosexuality will not inherit the kingdom. To reinforce the point, Paul adds a solemn warning, “Do not be deceived” (μὴ πλανᾶσθε). There were voices in the church seeking to deceive the Christians in Corinth on this very point. This can be detected in the libertine slogan, “All things are lawful” (6:12; 10:23), that Paul quotes and then refutes with the claims of the gospel. In 1 Corinthians 10:1–4, Paul warns them again, pointing to the example of the Israelites in the wilderness. They too had their version of the Christian sacraments. They too were baptized into Moses and ate spiritual food and drank spiritual drink. “Nevertheless,” Paul says, “with most of them God was not pleased, for they were overthrown in the wilderness” (10:5), and he goes on to warn the Corinthians against the same sins of sexual immorality and idolatry. He adds, “Therefore let anyone who thinks that he stands take heed lest he fall” (10:12). These warnings are not meant to imply that someone who is elect and savingly united to Christ can lose their elect status and fall out of union with Christ. They are meant to challenge those who profess faith in Christ, are members of the visible church, and partakers of the church’s sacraments not to presume on God’s grace and think they are going to be saved eschatologically even if they continue in unrepentant sexual immorality and idolatry.

The warning, “Do not be deceived,” is found two other times in Paul’s letters in contexts of the same literary form, that is, vice lists followed by warnings that those who do such things will not inherit the kingdom (Gal. 5:19–21 + 6:7–8; Eph. 5:5–7). This suggests that Paul’s strong “will not inherit” judgment applies even to professing Christians who continue in these sins without repenting. These are real sins that those who profess the name of Christ can commit. And if they persist in them without repentance, they will not inherit the kingdom of God.

From the Old Life to the New Creation

Paul has issued his solemn warning. He has said that those living an unrepentant life of immorality, idolatry, etc., will not inherit the kingdom of God. But in verse 11 he applies the gospel and assures the Christians in the church of Corinth that, though they were these things, they are such no longer: “And such were some of you. But you were washed, you were sanctified, you were justified in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ and by the Spirit of our God.”

“Such were some of you” (καὶ ταῦτά τινες ἦτε). The neuter plural ταῦτα (“such”) summarizes the preceding vices listed in verses 9–10 as more than incidental actions (e.g., one sexual misdeed) but repeated actions that have hardened into a person’s character (“the sexually immoral”). The imperfect verb ἦτε implies “continuous habituation.”[26] The sins listed in verses 9–10 were ongoing habits of life that defined who many of the Corinthians were. But the past tense, “were,” implies that they are no longer living that way. Thus, while the term “repentance” is not used here, the concept is implied by the statement, “such were some of you.” In other words, some of you used to live this way, but you don’t live that way any longer because you have become a new creation in Christ and have turned from the old life of sin.

“But you were washed, but you were sanctified, but you were justified” (ἀλλ’ ἀπελούσασθε, ἀλλ’ ἡγιάσθητε, ἀλλ’ ἐδικαιώθητε). The repetition of the strong adversative “but” has a powerful rhetorical effect. It further highlights the strong “before conversion” vs. “after conversion” temporal transition that has occurred in the life of these former pagans. They “were” these things. Their lives as pagans, before coming to Christ, were once characterized by these sinful patterns. But they have undergone a radical change. They have been converted by a monergistic act of God on the basis of Christ’s merit and through the applicatory work of the Spirit washing, definitively sanctifying, and justifying them.

The three verbs, “washed,” “sanctified,” and “justified,” are not given in any particular order, as if Paul is here laying down a technical ordo salutis.[27] We should not suppose that justification comes after washing and definitive sanctification. Instead, the three terms, like those in 1 Corinthians 1:30 (“righteousness, sanctification, redemption”), are thrown together to highlight the full-orbed nature of the gospel as including not only the forensic but also the transformative dimensions. It is a full salvation that we have in Christ. We are not only justified (deemed righteous); we are also washed, set free from the dominion of sin, and set apart as holy to God.

As already noted, there are two parallel passages where Paul makes the same “will not inherit” judgment (Gal 5:19–21; Eph 5:5). These two passages are just as strong as our text, and yet both of these are found in letters where Paul explicitly and emphatically teaches salvation by grace alone. Paul evidently did not see any inconsistency or tension between these two things: (1) we are saved, not by our own good works, or by being good and living righteously, but by faith in Christ (Gal 2:16; Eph 2:8–9), and yet (2) anyone who claims to be a Christian but who persists in defiant sexual immorality is not going to inherit the kingdom (Gal 5:19–21; Eph 5:5).

Paul teaches that progressive sanctification is not an optional extra in the Christian life, but an absolute necessity. He says, “If you live according to the flesh you will die, but if by the Spirit you put to death the deeds of the body, you will live” (Rom 8:13). Charles Hodge comments on this verse: “The necessity of holiness . . . is absolute. No matter what professions we may make, or what hopes we may indulge, justification, or the manifestation of the divine favour, is never separated from sanctification.”[28] The inseparability of justification and sanctification in Paul’s thought is implied in our very text: “But you were washed, you were sanctified, you were justified” (v 11). This presupposition stands behind the solemn warning (vv 9–10), and that is why the warning is not inconsistent with Paul’s doctrine of salvation by grace alone.[29]

Church Discipline (1 Cor 5:1–13)

We have seen the theological implication — those who continue impenitently in these sins will not inherit the kingdom. There is also an ecclesial implication — such sin must not be tolerated in the church. This ecclesial implication derives from reading 6:9–11 in light of the previous chapter, where Paul chastises the Corinthian church for failing to exercise proper church discipline in the case of a man who was sleeping with his father’s wife (1 Cor 5:1). He rebukes the Corinthians for becoming arrogant, when they ought to have mourned instead. He calls them to take decisive action: “Let him who has done this be removed from among you” (v 2). He calls on them to “cleanse out the old leaven” (v 7) by exercising church discipline. Paul then clarifies that he did not mean not to associate with the sexually immoral of this world, but with those who profess to be Christians:

But now I am writing to you not to associate with anyone who bears the name of brother if he is guilty of sexual immorality or greed, or is an idolater, reviler, drunkard, or swindler—not even to eat with such a one. For what have I to do with judging outsiders? Is it not those inside the church whom you are to judge? God judges those outside. “Purge the evil person from among you.” (1 Cor 5:11–13)

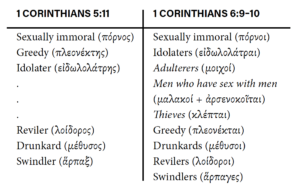

There is a high degree of overlap between the vice list in 5:11 and the vice list in 6:9–10. The word order is broadly similar, with two changes (“greedy, idolater” switched, and “reviler, drunkard” switched). Another difference is that 5:11 has the sins in the singular, while 6:9–10 has them in the plural. Also, several new sins (italicized) are inserted by Paul in the second list:

The two lists lead off with the same sin (“sexually immoral”) and end with the same sin (“swindlers”). The two lists are so similar, both in terms of the lexemes chosen and the way they are ordered, it is difficult to resist the inference that the second list intentionally links back to the first. By implication, the discussion of church discipline that surrounds the first list colors the second list. Paul’s injunction, “But now I am writing to you not to associate with anyone who bears the name of brother if he is guilty of sexual immorality,” etc. (5:11), implicitly calls the church to remove from its fellowship anyone living impenitently in the sins mentioned in 6:9–10.

The Divorce-and-Remarriage Challenge

Evangelical pastors and churches, out of reverence for Scripture, acknowledge that same-sex relations are not in line with God’s creation design for human sexuality. And yet they may wish to adopt a compassionate and pastoral stance toward the same-sex attracted Christian who struggles to manage romantic and sexual desires in chaste singleness. “Optimum homosexual morality” (Smedes) suggests that for such a person, it would be better to enter a committed same-sex relationship. On such a pastoral approach, the argument goes, the church could tolerate or accommodate committed same-sex relationships without fully endorsing them.

As we have seen, 1 Corinthians 6:9–11 presents a major hurdle for this reasoning. But evangelical accommodationists like Smedes attempt to overcome that hurdle by challenging the church with an apparent inconsistency in its application of this text. According to Jesus, second marriages are adulterous: “And I say to you: whoever divorces his wife, except for sexual immorality, and marries another, commits adultery” (Matt 19:9; cf. 5:32; Mark 10:11–12). Is the church really prepared to be consistent and exclude from the kingdom those who remarry after an unbiblical divorce? Accommodationists would point out that 1 Corinthians 6:9–10 explicitly mentions “adulterers” as among those unrighteous persons who are excluded from the kingdom. Jesus seems to be saying that those who have divorced for reasons other than unfaithfulness and subsequently remarried are living in adultery. Yet how many evangelical churches would bring church discipline against those who have remarried after an unbiblical divorce? By and large, evangelicals have already adopted a pastorally accommodating approach to some matters related to sex and marriage, recognizing that we live in a messy, fallen world, without denying the biblical ideal of marriage as a life-long union. Therefore, the argument goes, it would be inconsistent of the church to adopt a pastoral approach to the divorced-and-remarried but not to extend the same grace to those in same-sex relationships.[30]

How should we respond to the divorce-and-remarriage challenge? I would suggest that the words of Jesus need not be taken to imply that a second marriage after an unbiblical divorce is continuously adulterous. They need only be taken as implying that the inception of the second marriage is an adulterous act. If a divorce for a reason other than sexual immorality takes place, Jesus’ teaching mandates that those so divorced must remain single and not remarry. We can get at this issue from another direction by inquiring about the moral status of a second marriage. The key ethical question that must be addressed is this: When a person remarries after an unbiblical divorce, is the second marriage a valid marriage in the eyes of God? John Murray argues that it is:

Though illegitimate, it is a real marriage and should be regarded as such. It has the effect of dissolving the first marriage …. On this interpretation the second marriage should not be dissolved. Though contracted and consummated illegitimately and adulterously, it nevertheless de facto exists and the parties to it should prove faithful to each other.[31]

Murray’s language of a marriage “contracted and consummated illegitimately and adulterously” provides a helpful gloss of the words of Jesus. A man who divorces his wife for a reason other than unfaithfulness and marries another woman “commits adultery” (μοιχᾶται) in the sense that he contracts and consummates the second marriage illegitimately and adulterously. The present tense μοιχᾶται need not be taken in a continuous sense but as a gnomic present expressing a fact that always obtains whenever the conditions are met.[32] The adultery Jesus speaks of would then be limited to the initial conjugal act when the second marriage was consummated, not to every conjugal act thereafter. Since the divorce was on grounds other than adultery, the previous marriage was still in force in God’s eyes up to the moment of the initial conjugal act consummating the second marriage. But as Murray argued, the consummation of the second marriage “has the effect of dissolving the first marriage.” For those who have sinfully remarried, they ought not to compound their sin by getting divorced again, but rather to repent of their sin of getting remarried after an unbiblical divorce and to seek to remain faithful to the second marriage, even though it was sinfully contracted.

To be sure, impenitent adulterers are excluded from the kingdom (1 Cor 6:9–11), and the church must not tolerate those living in adulterous or sexually immoral relationships (1 Cor 5:1–13). But those who are penitent over their sin of contracting and consummating a second marriage after an unbiblical divorce are not living in a sexually immoral relationship. On this reading of Matthew 19:9 (and parallels), then, the divorce-and-remarriage challenge fails because the church is not in fact tolerating sexual immorality in the case of the divorced-and-remarried.

A Theologically Unstable Position

Marriage is a one-flesh union between one man and one woman, as revealed in the creation narrative (Gen 1:27; 2:24) and affirmed by Jesus himself (Matt 19:4–6). Crucially, Scripture assumes this definition of marriage and defines sexual immorality (πορνεία) as all sex outside of marriage (see the word study on πορνεία above; cf. Matt 19:3–9; 1 Cor 7:1–9; Heb 13:4). Since a same-sex relationship is not a real marriage in accordance with the word of God, same-sex relations within such a relationship constitute sexual immorality, and it doesn’t matter if the relationship is committed and exclusive. But this creates a problem for pastoral accommodation. For while accommodationists recognize that same-sex activity falls short of God’s ideal for sexuality, they cannot agree that same-sex activity within a committed relationship constitutes sexual immorality. They must argue that a committed same-sex relationship makes same-sex sex holy and not immoral, in the same way that real marriage makes heterosexual sex holy and not immoral. But this dramatically redraws the boundary between moral sex and immoral sex. That boundary, according to Scripture and the church’s traditional sexual ethic, is marriage. Sex within biblical marriage is moral. Sex outside of it is immoral. But those who hold the pastoral accommodation view end up creating a new category: moral sex outside of biblical marriage.

The new category of moral sex outside of marriage is theologically unstable. Accommodationists at heart want to be pastoral — and that is commendable. But in order to be pastoral, accommodationists will necessarily need to treat same-sex unions as practically identical to, or at least analogous to, real marriages. The same-sex couple will be called to physical and emotional faithfulness to one another. The church will need to hold them accountable to their vows of faithfulness. Partners who break their vows will have to be disciplined by the church as if they had committed adultery. Questions as to the legitimate grounds for divorce will have to be addressed. In churches that practice infant baptism, children will be brought to the church for baptism. The entire apparatus of the church’s pastoral care of and accountability toward real marriages will have to be extended to same-sex unions. If it is not, the accommodationist church would be admitting that the unions in question constitute sexual immorality in its eyes — a grave sin that, without repentance, requires church discipline. But church discipline is what pastoral accommodation is, by definition, seeking to sidestep. Thus, if the church does not want to treat same-sex relationships as sexually immoral, then it must treat those unions as if they were, for all practical purposes, tantamount to real marriages.

Churches and pastors that have adopted a policy of pastoral accommodation rarely remain there, eventually transitioning to full LGBT-inclusion and affirmation. For example, in 1978, the United Presbyterian Church in the USA acknowledged that homosexuality fell short of God’s design for human sexuality, yet advocated a compassionate, pastoral, and gradual approach, recognizing that the church is not a citadel of the morally perfect but a hospital for sinners.[33] Practicing homosexuals who confessed Jesus as Lord were not to be excluded from membership. The line was drawn at ordained office; homosexuals were eligible for ordination only if they experienced orientation change or remained celibate. But the line could not hold. If practicing homosexuals were welcomed as members, on what grounds could they be barred from ordination? Eventually accommodation became full affirmation. In 2011, the PC(USA) changed its standards so that persons in same-sex relationships are no longer ineligible for ordination.[34] In 2015, it changed the definition of marriage to include same-sex marriage.[35]

The evolution of the PC(USA) is a cautionary tale at the denominational level. An example at the individual level is the case of Reformed Church in America minister and professor, James Brownson. A few years after defending pastoral accommodation as a legitimate option,[36] he shifted further to the left and now defines marriage as a “one-flesh kinship bond” between two persons without regard to gender.[37]

Pastoral accommodation appears to be an unstable halfway house. It cannot last long. The logical endpoint is an affirming stance that views these unions as equivalent to real marriage, that is, as bestowing a mantle of moral legitimacy on same-sex relations just as real marriage does on opposite-sex relations. Pastoral accommodation, in spite of its claim to be an evangelical position that respects Scripture, recasts the traditional sexual ethic and inevitably redefines marriage itself.

Conclusion

In 1 Corinthians 6:9–11, Paul teaches that the salvation that is ours in Christ not only includes a judicial verdict of justification but also includes a radical transformation wherein our old way of life is changed and our lives are no longer dominated by sin. The dominion of the sins of the old, pre-Christian way of life, particularly sins pertaining to sexual immorality, is broken, and we are washed, set apart as holy, and set free to a new life in Christ. Those who profess the name of Christ but who persist without repentance in these sins are excluded from the kingdom. One of the sins that excludes from the kingdom is persistent same-sex practice. Pressure from the surrounding culture may push some evangelicals to seek to accommodate professing Christians in same-sex relationships as members of the body of Christ. Yet the explicit teaching of this text, penned by the inspired Apostle Paul, closes the door to pastoral accommodation. Same-sex relationships are sexually immoral (1 Cor 6:9–11). Sexual immorality cannot be tolerated in the church (1 Cor 5:1–13). Therefore, same-sex relationships cannot be tolerated or accommodated in the church.

Charles Lee Irons (Ph.D.) is a New Testament scholar with a focus on the letters and theology of Paul. Currently he is a senior research administrator at Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science. He is a member of and licensed to preach in the United Reformed Churches of North America.

[1] Jonathan Merritt, “A large Colorado congregation just became LGBT-inclusive. Here’s why it matters,” Religion News Service(January 26, 2017). https://religionnews.com/2017/01/26/colorado-congregation-joins-growing-list-of-lgbt-affirming-evangelical-churches

[2] Lewis B. Smedes, Sex for Christians: The Limits and Liberties of Sexual Living (Rev. Ed.; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1994), 57–58.

[3] Smedes, Sex for Christians, 239.

[4] Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are from the English Standard Version (2016 text edition).

[5] Some see 1 Cor 6:9–10 as a standardized list from a “dead” pre-formed tradition, but others have made a good argument for seeing each of the sins identified by Paul as of “live” concern vis-à-vis the situation at Corinth: B. J. Oropeza, “Situational Immorality: Paul’s ‘Vice Lists’ at Corinth,” ExpTim 110.1 (1998): 9–10; Peter S. Zaas, “Catalogues and Context: 1 Corinthians 5 and 6,” NTS 34.4 (1988): 622–29.

[6] David E. Garland, 1 Corinthians (BECNT; Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2003), 13–14.

[7] Garland, 1 Corinthians, 152–53, 198.

[8] Walter Bauer, Frederick W. Danker, William F. Arndt, and F. Wilbur Gingrich, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature (3rd ed.; Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2000) (= BDAG), s.v. πόρνος.

[9] Moisés Silva, ed., New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology and Exegesis (= NIDNTTE) (2nd Ed.; Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2014), 4.109.

[10] Franco Montanari, The Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek (= BrillDAG) (ed. Madeleine Goh and Chad Schroeder; Leiden: Brill, 2015), s.v. πόρνη, πορνεύω, πορνεία, πορνεῖον, πορνογενής.

[11] Kyle Harper, “Porneia: The Making of a Christian Sexual Norm,” JBL 131.2 (2011): 370.

[12] Silva, NIDNTTE, 4.111.

[13] Joseph Jensen, “Does Porneia Mean Fornication? A Critique of Bruce Malina,” NovT 20.3 (1978): 161–84.

[14] The Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs is a writing of Hellenistic Judaism dated during the Hasmonean period (167 BC–63 BC).

[15] The Matthean exception clause only makes sense if the term πορνεία is broad enough to refer to adultery. Donald A. Hagner, Matthew 1–13 (WBC 33A; Dallas: Word Books, 1993), 125; Harper, “Porneia,” 375–76.

[16] Paul uses πόρνος six times (1 Cor 5:9, 10, 11; 6:9; Eph 5:5; 1 Tim 1:10). The word occurs in other parts of the NT four times (Heb 12:16; 13:4; Rev 21:8; 22:15).

[17] Walter Bauer, Frederick W. Danker, William F. Arndt, and F. Wilbur Gingrich (BDAG), A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature (3rd ed.; Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2000), s.v. πόρνος; Johannes P. Louw, Eugene A. Nida, Rondal B. Smith, and Karen A. Munson, Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament Based on Semantic Domains, 2 Vols. (2nd Ed.; New York: United Bible Societies, 1989), s.v. πόρνος (§88.274).

[18] However, the feminine form, πόρνη, still means “female prostitute” in the NT (12x).

[19] James D. G. Dunn, The Theology of Paul the Apostle (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), 690; E. P. Sanders, Paul: The Apostle’s Life, Letters, and Thought (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2015), 365–66.

[20] BDAG s.v. μαλακός, ἀρσενοκοίτης.

[21] David F. Wright, “Homosexuals or Prostitutes? The Meaning of ΑΡΣΕΝΟΚΟΙΤΑΙ (1 Cor. 6:9, 1 Tim. 1:10),” Vigiliae Christianae38 (1984): 125–53; Robert A. J. Gagnon, The Bible and Homosexual Practice: Texts and Hermeneutics (Nashville: Abingdon, 2001), 303–39.

[22] Plutarch, Erōtikos [Amatorius] 751D; Philo, Spec. 3:37–40; Abr. 135–36.

[23] Sanders, Paul, 367; Robin Scroggs, The New Testament and Homosexuality: Contextual Background for Contemporary Debate (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1983), 83, 86, 108; Wright, “Homosexuals or Prostitutes?”

[24] Sanders, Paul, 366–68.

[25] “The list starts with pornoi in the sense of ‘the sexually immoral,’ followed by the other main gentile sin, idolatry, followed by specific kinds of sexual immorality” (Sanders, Paul, 365). Cf. 1 Tim 1:10 where “the sexually immoral, men who practice homosexuality” (πόρνοι, ἀρσενοκοῖται) are juxtaposed.

[26] Thiselton, First Corinthians, 453.

[27] “The order of the verbs . . . has no theological significance.” Garland, 1 Corinthians, 216.

[28] Charles Hodge, Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans (Rev. Ed.; Philadelphia: James S. Claxton, 1864), 415 (p. 264 in The Banner of Truth edition).

[29] Calvin similarly argues that the twin blessings of salvation (justification and sanctification) are inseparable. Institutes 3.16.1.

[30] The divorce-and-remarriage challenge is raised by Smedes in “Like the Wideness of the Sea?” Perspectives 12 (May 1999): 8–12. Reformed Church in America minister and NT professor, James V. Brownson, picks up Smedes’s argument in “Gay Unions: Consistent Witness or Pastoral Accommodation? An Evangelical Pastoral Dilemma and the Unity of the Church,” Reformed Review 59.1 (2005): 3–18.

[31] John Murray, Divorce (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 1961), 111.

[32] Daniel B. Wallace, Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1996), 523.

[33] “The Church and Homosexuality,” Louisville, KY: Office of the General Assembly of the United Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, 1978, https://www.pcusa.org/site_media/media/uploads/_resolutions/church-and-homosexuality.pdf.

[34] Jerry Van Marter, “PC(USA) relaxes constitutional prohibition of gay and lesbian ordination,” Presbyterian Church USA (May 11, 2011), https://www.pcusa.org/news/2011/5/11/pcusa-relaxes-constitutional-prohibition-gay-and-l.

[35] Patrick D. Heery, “What same-sex marriage means to presbyterians,” Presbyterian Church USA (March 20, 2015),https://www.pcusa.org/news/2015/3/20/what-same-sex-marriage-means-presbyterians.

[36] See note 30 above.

[37] James V. Brownson, Bible, Gender, Sexuality: Reframing the Church’s Debate on Same-Sex Relationships (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2013), 85–109.

You, too, can help support the ministry of CBMW. We are a non-profit organization that is fully-funded by individual gifts and ministry partnerships. Your contribution will go directly toward the production of more gospel-centered, church-equipping resources.